'Awful to be there': Former refugee's struggle in notorious emergency housing

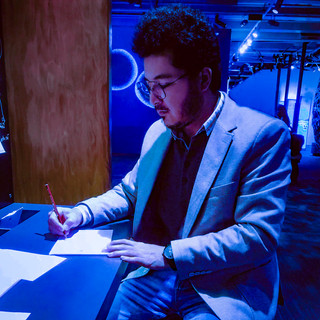

- Abdul Samad Haidari

- Jun 30, 2024

- 7 min read

Hanna McCallum

April 15, 2023, • 05:00am

Hazara-Afghani journalist and poet, Abdul Samad Haidari, was put in Wellington’s notorious emergency housing after arriving in New Zealand after close to a decade in Indonesia as a stateless refugee.

DAVID UNWIN / STUFF

Abdul Samad Haidari’s move to New Zealand was supposed to be a fresh start to a shattered life.

He had fled persecution from Taliban in his home country, Afghanistan, then spent nearly a decade in Indonesia as a stateless refugee with no rights.

Being granted residency in Aotearoa on humanitarian grounds should have been a game-changer.

Instead, Haidari was put in a notorious emergency housing motel, living on tinned food with flies swarming around a stuffy, dim room.

READ MORE:* Refugee lives told through prose* New Zealand's Afghanistan Legacy* Muslim refugees resettled in Christchurch after terror attacks hold no fears

While at pains to point out he is grateful to be here, it felt no different to the refugee camps and precarious accommodation he’d lived in for much of his life.

“It feels exactly the same ... I’m still the refugee that I was in Indonesia.”

The relative levels of safety in New Zealand hasn’t eased the unsettling feeling emergency accommodation continued to stir in him.

The Hazara-Afghani journalist and poet has moved three times since arriving in February. About three weeks were spent at The Setup on Dixon in central Wellington.

Haidari will soon move into permanent accommodation, but his time at The Setup still affects him. It felt like it was “night 24 hours”. “You don’t see the outside world.”

“Me, as a newcomer, I have nothing,” Haidari says. “It was awful to be there.”

A lack of hygiene was evident from the smells in the bathroom and his room. He was unable to open his window because of rubbish outside and the swarms of flies that would fill his room.

Haidari has spent much of his life moving across borders after fleeing from the Taliban in Afghanistan as a young child and is grateful to be resettled in Aotearoa.

DAVID UNWIN / STUFF

Vomit was left in the elevators for at least two days and the bathrooms frequently flooded, covering the floors in pools of water.

With no cooking utensils, Haidari lived on tinned food while fasting for Ramadan.

Since inquiries from Stuff the Ministry of Social Development (MSD), has said the accommodation provider will now provide cooking utensils.

Wellington regional commissioner Gagau Annandale-Stone said emergency housing was a last resort.

“But if it’s a choice between sleeping in two or three-star accommodation or outside in a car, we consider the former preferable.”

A report released by the Human Rights Commission last year found the Government’s emergency housing system was in breach of the human rights of those it aimed to help.

Before The Setup, Haidari spent some time in private accommodation in Johnsonville – in a room that could not be locked from the inside and only a thin blanket to sleep under.

After The Setup, he was moved to a room at the Quest Hotel after raising concerns with his MSD case manager.

Daphany Haenga has lived at The Setup on Manners twice over the last six months.

Following the complaint, MSD staff visited The Setup and were told two reports of toilets being blocked were resolved within the day, building elevators were cleaned every day and cleaning staff regularly sprayed to deter flies and bugs from the building, Annandale-Stone said.

She expected accommodation suppliers to meet all relevant standards imposed by regulatory authorities – something that was being reviewed after Cabinet agreed to implement 10 actions from its own internal review last December.

Associate Minister for Social Development and Employment Priyanca Radhakrishnan said work had begun and it was developing standards for minimum expectations around safety and suitability of emergency housing.

Between the end of November 2021 and February 2023, the number of households in emergency housing nationally had fallen by 33%, Radhakrishnan said.

However, the amount of time people spent in accommodation could span more than a year – far longer than the short-term accommodation it was designed to be when it was first introduced in 2016.

At the end of 2022, 198 households were living in emergency housing in Wellington City, according to MSD data.

Abdul’s journey to Aotearoa

Born in Dahmardah in Ghazni province, Afghanistan, Haidari and his family were forced to flee from the Taliban in the late 1990s, following the bombing of their home in which he lost his younger sister.

The family split up to avoid “collective death” and eventually Haidari was on his own.

Haidari is overwhelmed by the support he has received from new friends in the community, but is falling through the gaps of official support.DAVID UNWIN / STUFF

“I was this tall,” he says, putting his hand out at about shoulder height, sitting down in a chair.

“Maybe 9, 10, 11 ... no more than 13.”

He spent time in a detention camp in Iran where he witnessed people being tortured and spent days sitting in the corner of the “crowded, crowded camp”, crying.

“I was scared of that environment and I was scared of everyone – I just wanted to be with my father.”

Not long after, he worked as a child labourer at a construction site. His nights were spent sleeping under mulberry trees, quietly crying himself to sleep.

He had made “traumatising” journeys between cities and across borders, often travelling under bus seats between baggage to stay hidden.

On one occasion, the bus he was travelling in was stopped by the Taliban. Haidari and other Hazara people – one of the country’s most persecuted ethnic groups – were selectively taken off the bus and made to stand in a “shooting line”.

“They shot two of them and I was rescued by an elderly Pashtun woman. When they shot [one man], the blood splashed my face … I survived that one.”

Coming to Aotearoa allowed Haidari to dream of rebuilding a life with security and he hopes to be able to bring his family to join him – something that would be the ultimate healing.

DAVID UNWIN / STUFF

Eventually in 2007, Haidari returned to Afghanistan where he began work as a journalist and humanitarian aid worker, writing for the Daily Outlook Afghanistan and the Daily Afghanistan Express.

As a Hazara-Afghani person, he reported the war crimes and brutality, perpetrated by the Taliban on the minority group. Writing was an act of resistance and survival, Haidari says.

But reporting at the time was like being in a battlefield.

Journalists and their families were targeted and Haidari was stabbed in the leg in 2013, along with another colleague.

We were not creating war, we were telling the truth – but I had to pay a lot of price for that. I lost my father because of my journalism.”

Eventually he was forced to seek asylum and ended up in Indonesia in 2014.

When it became apparent he couldn’t practice journalism, he shifted his focus to poetry, also writing about the unfair treatment of refugees in Indonesia.

As a refugee, Haidari had no right to work, access to public health, education, and was not being considered for resettlement.

MORE FROM

HANNA MCCALLUM • REPORTER

He recalled living in a small room next to a river and jungle in Indonesia where he spent almost three years. Surviving only on rotten scraps of food, thrown out by a nearby store, he would often faint.

His book of poetry, The Red Ribbon, written during his time in Indonesia, was published – but only manuscript, not the final version – which he believes was politically motivated.

A second book, with “no censorship”, is under way.

Haidari still fears for the safety of his family and hopes to be reunited with them after 11 harrowing years apart.

“Most of my life has been wasted, running here and there across the borders ... every step of life built another layer of trauma in me. I’m expecting some healing; some space to heal and gather myself.”

‘It holds people back and keeps people down’

Jacqueline Wilton, ChangeMakers Resettlement Forum general manager, says it is a human right to have secure housing.

Experiences like Haidari’s make it difficult for migrants to live a “wholesome, healthy life”, as well as heal from any trauma they may have had.

“It holds people back and keeps people down, further marginalising.

ChangeMakers Resettlement Forum general manager Jacqueline Wilton says adequate housing is just one of many barriers faced by former refugees in Aotearoa.

KEVIN STENT / STUFF

“The whole idea of settlement is participation and inclusion and I just think if you can’t open your window and it’s an unhealthy environment, that’s not going to happen.”

But it is just one of many barriers faced by former refugees, she says.

Wilton has worked in the sector for more than 15 years and says many of those barriers have not been adequately addressed. They include discrimination, language barriers, a lack of community or family networks, and navigating a different culture.

Often overseas skills and experiences are not recognised – a significant barrier to finding work. Some also carry “survivor’s guilt”, having left friends and family behind in their home countries.

“Everybody coming in has challenges, they left their home,” Wilton says. “They haven’t made a choice to leave, they had to leave.”

Haidari says his new housing is “peaceful” and clean, allowing him to cook meals.

He has also felt overwhelming support from people in the community, with many reaching to provide support.

But the barriers he’s faced since arriving have been draining, affecting his ability to find a job and move off a benefit.

“It takes away the sense of freedom, a sense of joy.”

Haidari was granted residency under ministerial discretion on humanitarian grounds.

Bernard Sama, board chair of the Asylum Seekers Support Trust and PhD student at Auckland University.

SUPPLIED / STUFF

He has right to work and access public services like education, healthcare and the emergency benefit. But not being recognised as a refugee meant he was not given the same support as a quota refugee.

Bernard Sama, a former refugee and chairperson the Asylum Seekers Support Trust, says there is irony in being granted residency on humanitarian grounds, yet not receiving adequate support on arrival.

“It’s not sufficient and often it takes the goodwill of people they meet.”

Sama fled political persecution in Cameroon as an Anglophone rights activist, arriving in 2006 as an asylum seeker.

He spent time living with a Congolese refugee community in Hamilton, after being denied housing support.

“For many people, they want to get on with their lives ... We haven’t come here just to be on the benefit.”

In 2021, refugee advocates formed the Refugee Alliance, demanding the Government review the New Zealand Refugee Resettlement Strategy and the Migrant Strategy, approved in 2012.

As it stands, only quota refugees – those who have been selected offshore and resettled in Aotearoa under the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) system – are covered by the strategy, receiving adequate support.

The strategy is under review and the group is advocating for all refugees to be covered.

Haidari’s case is just another example of people falling through gaps in the system, Sama says.

Source: Stuff

Comments