Indonesia - Friendly transit point, never a homeThis article was published in thejakartapost.com with the title "". Click to read:

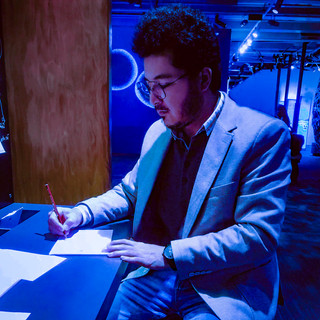

- Abdul Samad Haidari

- Jun 30, 2024

- 3 min read

Updated: Jun 30, 2024

A book opens up a new discussion on the myriad of problems faced by refugees and asylum seekers in Indonesia.

Tertiani ZB Simanjuntak (The Jakarta Post)

Jakarta Mon, March 13, 2017

Troubled Transit: Asylum Seekers Stuck in Indonesia by Antje Missbach (Shutterstock/File)

"I know a mysterious place, a place where nothing and everything is possible — in one way or another, a place where a drop of tear destroys a day-long laughter.”

That is the last part of a poem titled A Mysterious Place, I Know written by Abdul Samad Haidari, an Afghan former freelance journalist and a poet that represented the persecution faced by some 14,700 refugees and asylum seekers in Indonesia.

If the home countries they fled from are some sort of hell on earth, Indonesia as a transit country is not a haven either.

These pressing issues were revealed at a book launch and discussion about the plight of refugees and asylum seekers in Indonesia, organized by Germany’s Goethe-Institut on Feb. 23.

The event was opened by the poem reading by Haidari himself, who currently lives as a refugee in a community shelter in Bogor, West Java. The event launched the Indonesian translation of Troubled Transit: Asylum Seekers Stuck in Indonesia, authored by German-Australian anthropology lecturer Antje Missbach of Monash University.

More than half of the refugees from 49 countries, including Afghanistan, Somalia, Iran, Iraq and Myanmar, were asylum seekers. Most of them had to wait for two years to get an interview with the UNHCR and were still in limbo waiting for good news.

The fewer resettlements to Australia due to the country’s latest immigration policy and the fact that Indonesia lacked a comprehensive legal framework for refugee protection exacerbated the uncertainty, added Missbach.

“Indonesia is not a signatory to the 1951 International Refugee Convention, so the country does not offer local integration for refugees, but allows only for resettlement to a third country or voluntary repatriation,” she said.

Another speaker, human rights activist Rizka Argadianti Rachmah, said Presidential Regulation No. 125/2016 on the treatment of refugees from foreign countries, passed last December, was the only piece of legislation that adopted the 1951 Convention, which distinguished refugees from undocumented immigrants.

“The regulation, however, is more of a technical guideline on step-by-step procedures for the authorities in handling the refugees as soon as they reach Indonesian shores,” said the coordinator of SUAKA, a non-profit organization concerned with refugee’s rights that currently focuses on the Rohingya people of Myanmar being sheltered in Aceh; Medan, North Sumatra; Makassar, South Sulawesi; Jakarta; as well as in Bogor and Depok, West Java.

The absence of a solid legal framework, according to her, put the refugees in another misery without access to work or education for the children as well as legal protection during an uncertain period of stay.

“It’s still far from the ideal condition of providing the refugees with basic rights,” said Rizka.

Pakistan-born health activist Kalsoom Jaffari, who lives as a refugee in Cisarua, Bogor, since 2013, said the lack of activities at community shelters affected both mental and physical health of the refugees.

Once an aid worker for Afghan refugees in Pakistan who ended up a refugee herself, she initiated the Refugee Women Support Group, which held a series of women-focused workshops on health, hygiene and education in an informal setting.

Funded by donors, the group also opened art and handicraft classes, English lessons and sewing projects for the female refugees and the children to channel their creativity and intellect.

“Initially, they were idle and homebound, and that led to some health problems and domestic violence. By living an active lifestyle and learning new skills, the refugees are more convinced about being approved for resettlement to another country,” said Jaffari, the last speaker at the discussion.

The textile products, labeled Beyond the Fabric, have been in demand overseas and generated income for the refugees.

“Through this group, the refugees that come from different countries and ethnicities became friends and aware of other cultures as we also interact with our Indonesian neighbors. When they come to class, they forget their problems and instead talk about future plans. These activities give us purpose,” Jaffari added.

Source: TheJakartaPost

Comments