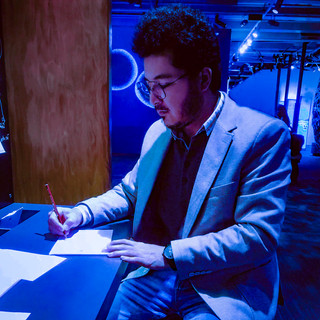

Review: The Unsent Condolences by Abdul Samad Haidari (Palaver 2023)

- Abdul Samad Haidari

- Jun 30, 2024

- 3 min read

by Aileen Crowe

Although I have listened to many traumatic refugee experiences, I realise how bereft I have been for the feelings of a person escaping unprecedented violence. The poems of Abdul Samad Haidari have drawn me into the heart of trauma.

Haidari is a gifted poet whose autobiographical poems, collected in The Unsent Condolences, have been written mainly during a decade spent in incarceration and ‘limbo’ in Indonesia. For the most part, as he states himself, the poetry has no rhyme, but it has rhythm – the rhythm of ‘being present’; drawing us into the lives of a person, a family, tormented members of one minority group within society. In telling us how it is, Abdul’s adeptness allows us to be horrified at distressing loss and dispossession. He beseeches us to hear ‘children scream, running in unending circles across the smoky fields’; to be terrified with him ‘as each rocket and missile lands’; to feel what it is like to powerlessly see the elderly falling and pulling themselves up only to fall again.

Haidari’s poems illustrate how deep pain resides in the soul and emerges from time to time in vivid violent imagery – ‘Past traces cleave in like shattering blades of swords, unzipping the fatal fist of old wounds, fresh as yesterdays’. The suffering is palpable. The trauma, a life sentence. The poems drew me in to refugee trauma as no news clip or documentary has ever done. For the inexperienced such a life is almost incomprehensible, for displaced people Haidari’s rhythm of loss and trauma validate their personal, painful claims of dispossession. These unrelenting sufferings sit uncomfortably in the luggage of many a person arriving at our borders seeking Australia’s protection.

Haidari in his final poem describes himself among other things as ‘a singer of unrhymed songs’. His poetry draws us into a sense of wonder despite the rawness of the horrors of his lived experiences. He exudes an inner power ever calling him to be greater than the traumas of ‘Nightmares unwrapped… leaping against the heavens’. The Unsent Condolences express an existence that is full of contradictions and yet, deep within, Haidari’s spirit recognises that his life is what it is. He attempts to negotiate the awfulness of horrific dispossession without being crucified by it.

Moving through and emerging from an unimaginable journey of violence Haidari’s poems are reflections on endurance, courage, raw emotion. They are rich in spirituality. While he has a communal awareness of the universality of God, his faith is unique, his relationship with God, profound: ‘I am but a pure nature, beholding the visage of God in it’. As he was running from smoke and fire ‘risen from the depths of hell’ he heard ‘screams that could shake the heart of God’. He realises that ‘All swallow sorrows … as their mournful mouths slowly whisper prayers for a safer place to hide’. He ponders how ‘God’s face is veiled in intimate thought’ and contemplates how ‘God drizzles slowly, seems tired – must be running out of tears’. Desolately Abdul writes: ‘The rug of union with God is ripped from our souls’. Wearily he declares, ‘I too pray and weep’ as he desperately cries out, ‘O God, tell borders to be kinder’.

Abdul’s dialogue with nature is interfaced with his horrific experiences and the depth of his relationship with God. Different aspects of nature are woven through the inexorable pain. He contemplates how ‘No soil is unfamiliar to Afghanistan bones’. He muses how ‘Tree’s ears can overhear; thorny bushes have eyes’ and ponders how ‘Earth is my king-sized home, valleys my chest, mountains my shoulder; hillsides my forehead’.

Following ‘a journey of the sane through the horrors of war, sea voyage, and camps’ there is the enduring struggle to feel at home in countries foreign to them. Overwhelmed with the trauma that sits uncomfortably in their hearts like ‘a bowl of raw meat on the tables of the wicked’ dispossessed, people seeking protection can feel like ‘Labelled guests whose existence is forbidden’.

This ode to horrific trauma is gift to the uninitiated. It begs to be absorbed. The reward – a deeper knowledge of the spiritual nature of the tortured souls that knock at the borders of our hearts seeking understanding rather than rejection, trust instead of fear, community embrace rather than discriminatory suspicion. A meditation that will break our hearts and redeem our souls.

Aileen Crowe is the author of Acts of Cruelty: Australia’s immigration laws and experiences of people seeking protection after arriving by plane (Palaver 2022)

Source: CatholicOutlook

Comments